PODCAST

TRIVIAL GAME: HISTORY

In the early 19th century, at a time when science was dominated by men, a young woman discovered fossil remains that transformed our understanding of the history of life on Earth. Her discovery of prehistoric marine creatures was fundamental to the birth of modern paleontology.

Who was this pioneer who defied the conventions of her time?

In our podcast ‘Historias de la Prehistoria‘ you can hear more about her story.

TRIVIAL GAME: HISTORY

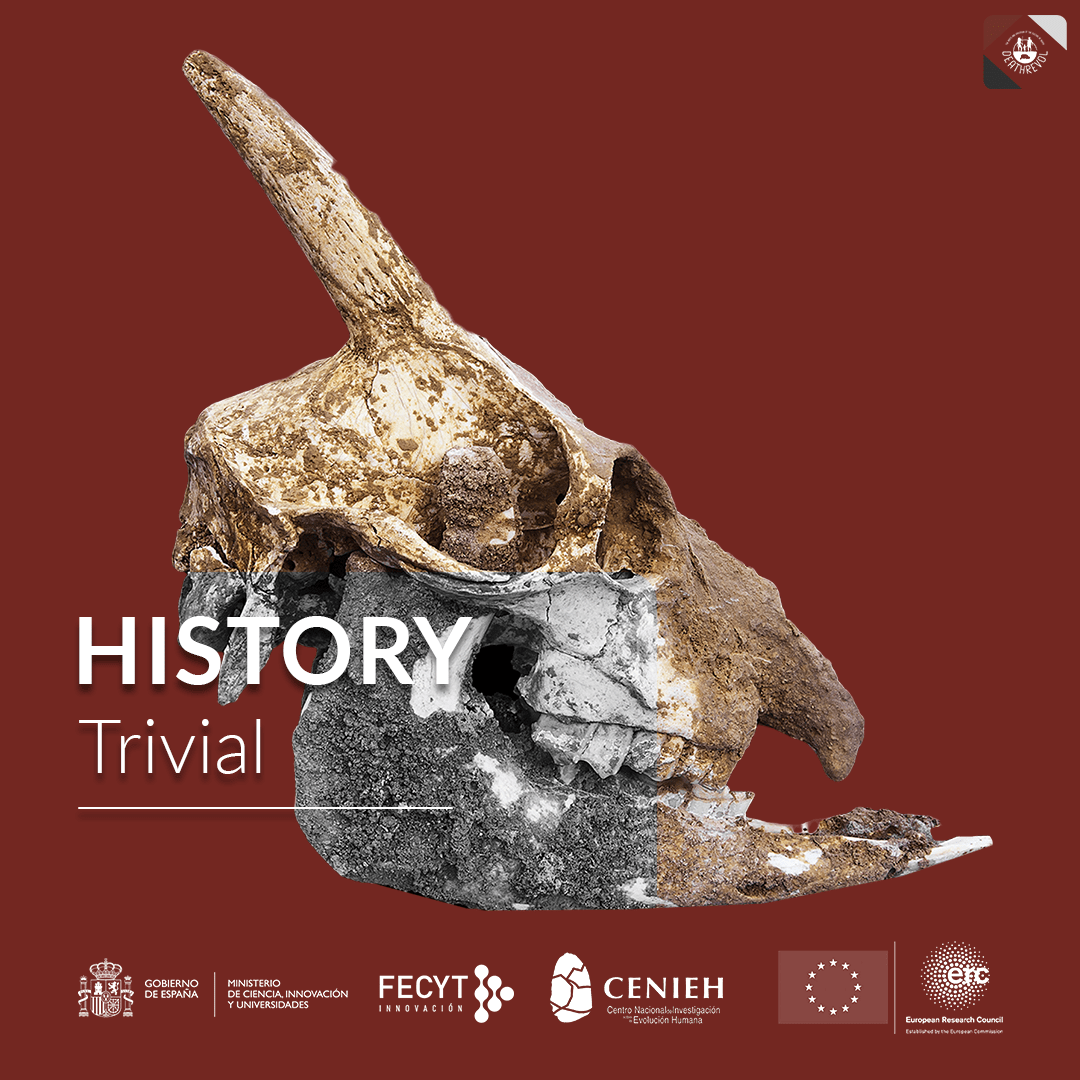

Who discovered the species 𝘔𝘺𝘰𝘵𝘳𝘢𝘨𝘶𝘴 𝘣𝘢𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘤𝘶𝘴?

Listen to episode 6 of our podcast “Historias de la Prehistoria” to learn more about Dorothea Bate and her valuable contributions to the world of science.

Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0

WHAT CAN WE DESCRIBE THROUGH TAPHONOMY?

Taphonomy, derived from the Greek “taphos” meaning “burial”, and “nomos” which translates to “law”, is a fundamental discipline for unraveling the mysteries surrounding the fossil deposits. Situated at the intersection of geology and biology, this discipline is devoted to the meticulous analysis of the processes governing fossilization and seeks to discern the causes behind the formation of fossil accumulations.

By examining bone assemblages from a taphonomic perspective, we can decipher a wide range of processes, from carnivore tooth marks to anthropic cut marks, as well as other signals left by biological or geological agents. The fractures present in bones also provide valuable information about their history, indicating when and how they were generated. It is through the interpretation of these data that we can reconstruct past events, understand the processes involved, and in some way, step back in time, akin to investigators at a crime scene.

MORTUARY AND FUNERARY BEHAVIOR

There are indications that some animals may have mortuary behaviour. Some primates, such as chimpanzees or gorillas, may show changes in their usual behaviour such as staying near the carcass for a period of time, cleaning the teeth of the corpse, or even mothers carrying the carcass of a dead calf for weeks. As time passes, they end up leaving the lifeless body and that activity ceases forever.

Other species, such as dolphins or elephants, also develop specific behaviours with the corpses of their relatives such as looking at, touching or even transporting the corpse for a while. This type of behaviour is fascinating, but it is not considered funerary behaviour, but mortuary. Do you remember the differences between these behaviours?

Death is an experience shared by all living things, but only people honor the dead with funeral rites. Unlike mortuary behaviour (related to the treatment of the body after death), funeral behaviour is a ritual, symbolic activity, characterized by having two components: space and time. Humans create spaces for the dead. In addition, we honor the death and maintain a link with them over time, commemorating the deceased through rites. In this way, a natural process (death) becomes a cultural process, which with different mortuary manifestations, is common to all human cultures that currently inhabit the planet.

The culture of death is a common and exclusive axis of human beings, but, when did our ancestors begin to acquire a culture of death? Listen to our podcast “Historias de la Prehistoria” to learn more!

HOLOTYPE: HOMO NEANDERTHALENSIS

A holotype is a physical specimen of an organism used when the species is first described.

In 1857 Professor Hermann Schaaffhausen published the analysis of the fossil remains rescued from a German quarry: the upper part of the cranium or calvaria, the ulnae, the femora, the radii, and fragments of the innominate bones, a scapula, a clavicle and some ribs. His conclusions were disconcerting, the morphology of the cranium was different from everything that was known at the time, particularly the strange morphology of his orbital torus.

In 1864, William King reviewed the morphology of the bones and proposed that it was a new species of humans that were named Homo neanderthalensis (man of the Neander Valley). Thus the Neandertals were born in the scientific literature.

The fossils of this specimen are known as Neandertal 1, and thus became the type specimen of this species.

MOUNT CARMEL

Mount Carmel is a limestone hill rising just over 500 meters above sea level on the Mediterranean coast of northern Israel, near Haifa. Its caves have provided valuable information, especially during excavations conducted between 1929 and 1934 by Dorothy Garrod in the Tabun and Skhul caves.

In Tabun cave, Garrod and her team unearthed a stratigraphic sequence spanning a wide chronological range. Among the most notable discoveries is the nearly complete skeleton of Tabun 1, assigned to an adult Neanderthal female with an estimated chronology of 120,000 years. She was found lying on her left side in a pit dug into the cave floor. It is considered one of the oldest Neanderthal burials in the fossil record. Tabun 2 is a mandible interpreted as belonging to a male individual.

Just a few meters from Tabun lies the cave of Skhul, where Garrod’s team found numerous pits excavated in the floor of the cave’s vestibule, containing 10 individuals, including adults and children, but with a crucial difference: they were not Neanderthals, but Homo sapiens. Although the individuals at Skhul shared geographic proximity and a similar archaeological context with those at Tabun, their anatomy marked a distinction.

These findings raise significant questions about the relationship between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the region, suggesting the potential for coexistence and interaction between the two species.

THE TAUNG CHILD

The fossil dubbed the Taung Child is the type specimen of its species, Australopithecus africanus. The skull exhibits a combination of human and ape-like traits and retains deciduous teeth, providing valuable information for estimating the approximate age at death, which was established between 3 and 4 years old. During fossilization, sediment saturated with calcium carbonate-rich water filled the skull, allowing for the preservation of a replica of the brain as it petrified. The marks present on the skull have been likened to those found on bones discovered in the nests of large raptors, such as eagles. This discovery suggests the possibility that the individual was captured by an eagle and taken to its nest for consumption.

If you find this content interesting, you can not miss our podcast “Historias de la Prehistoria“!

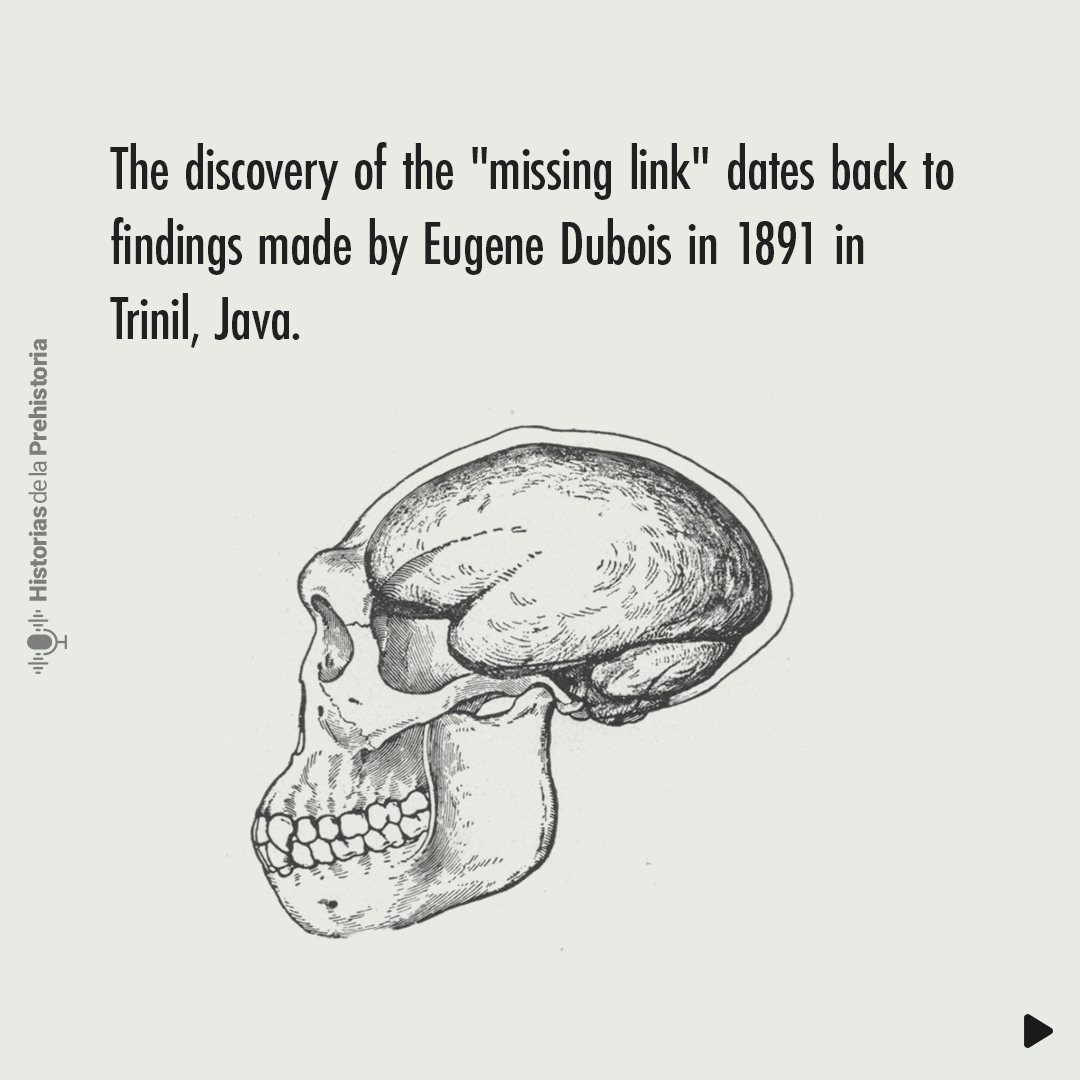

THE MISSING LINK

Once the theory of evolution is accepted, some people start looking for the ancestor of humans. Listen to our podcast “Historias de la Prehistoria” on Spotify to find out more about this “missing link”.

IT CHANGED EVERYTHING: CHARLES DARWIN

At just 22 years old, Charles Darwin embarked on a transformative journey that lasted nearly five years and took him to explore remote corners of the world. During the voyage, Darwin not only collected samples of native fauna and flora but also made crucial observations that would later inspire his theory of evolution. Along the Argentine coast, he unearthed fossils of extinct creatures such as the megatherium and the glyptodon, which led him to question the predominant theories of his time. Furthermore, his observations on the differences between species of rheas intrigued him and led him to reflect on the relationship between species and their environment. His courage and curiosity led him to explore still unknown regions, such as the Santa Cruz River and the channels of Tierra del Fuego, where he encountered cultures and landscapes that deeply impacted him.

During his stay on the Galápagos Islands, Darwin was fascinated by the diversity of species he found. He observed that tortoises, finches, and other creatures varied significantly from one island to another, sowing the seed of his idea about evolution and natural selection. These discoveries would play a crucial role in the subsequent development of his revolutionary theory.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to learn about the origins of humanity: start listening to our podcast “Historias de la Prehistoria” today!