Divulgation

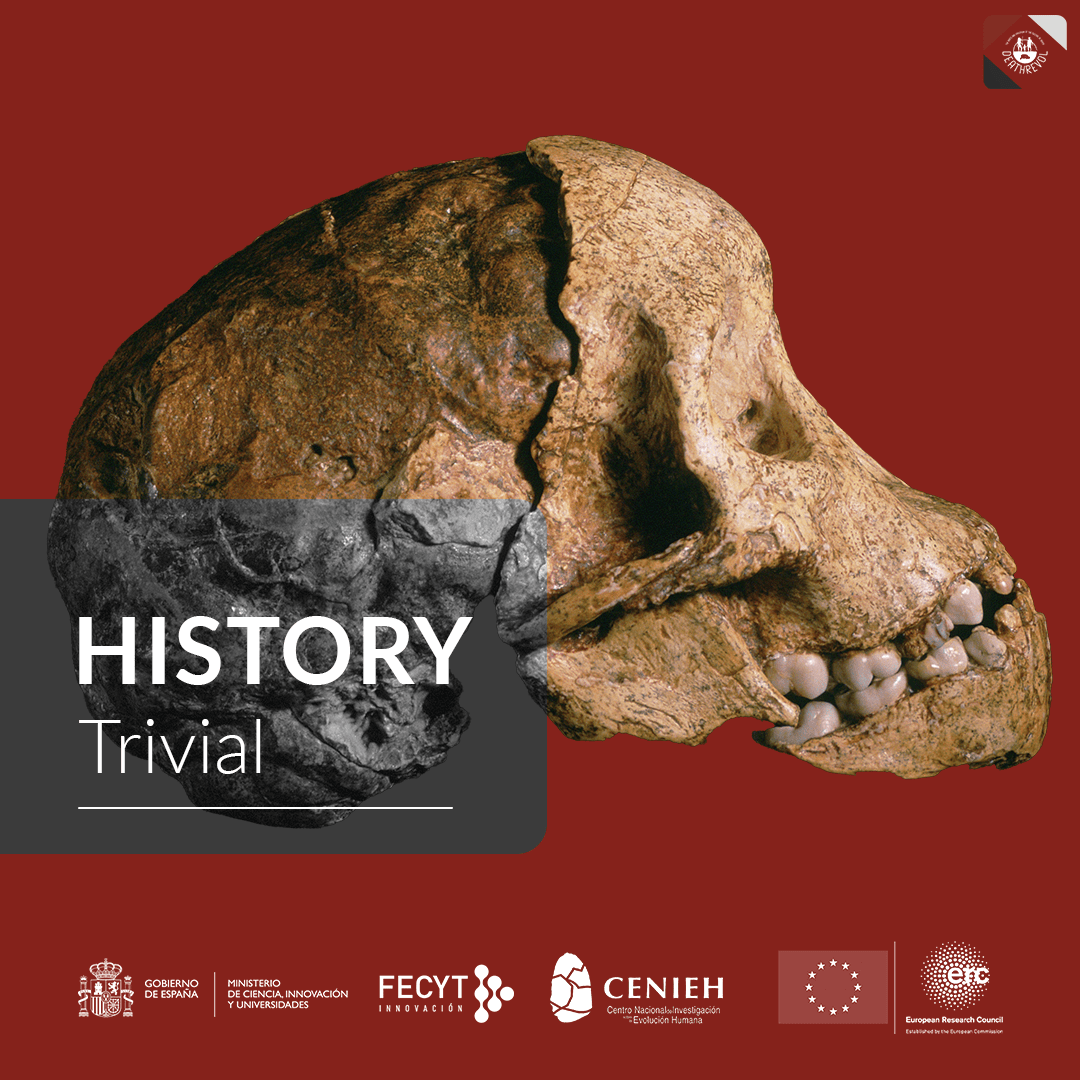

TRIVIAL GAME: HISTORY

Who discovered the fossil known as the Taung Child? Here you can read the answer!

Also you can listen to episode 5 of our podcast “Historias de la prehistoria” to learn more about this find.

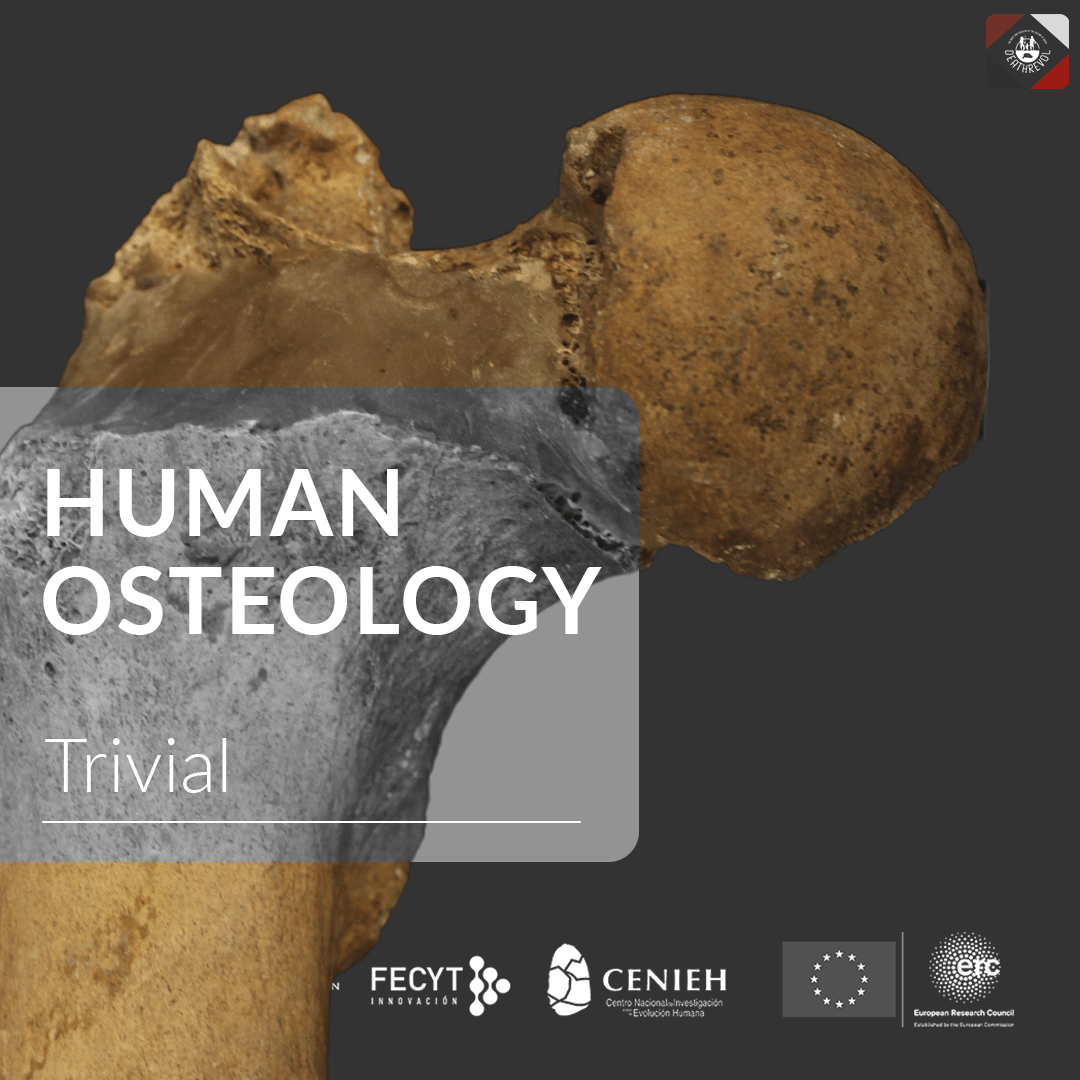

TRIVIAL GAME: OSTEOLOGY

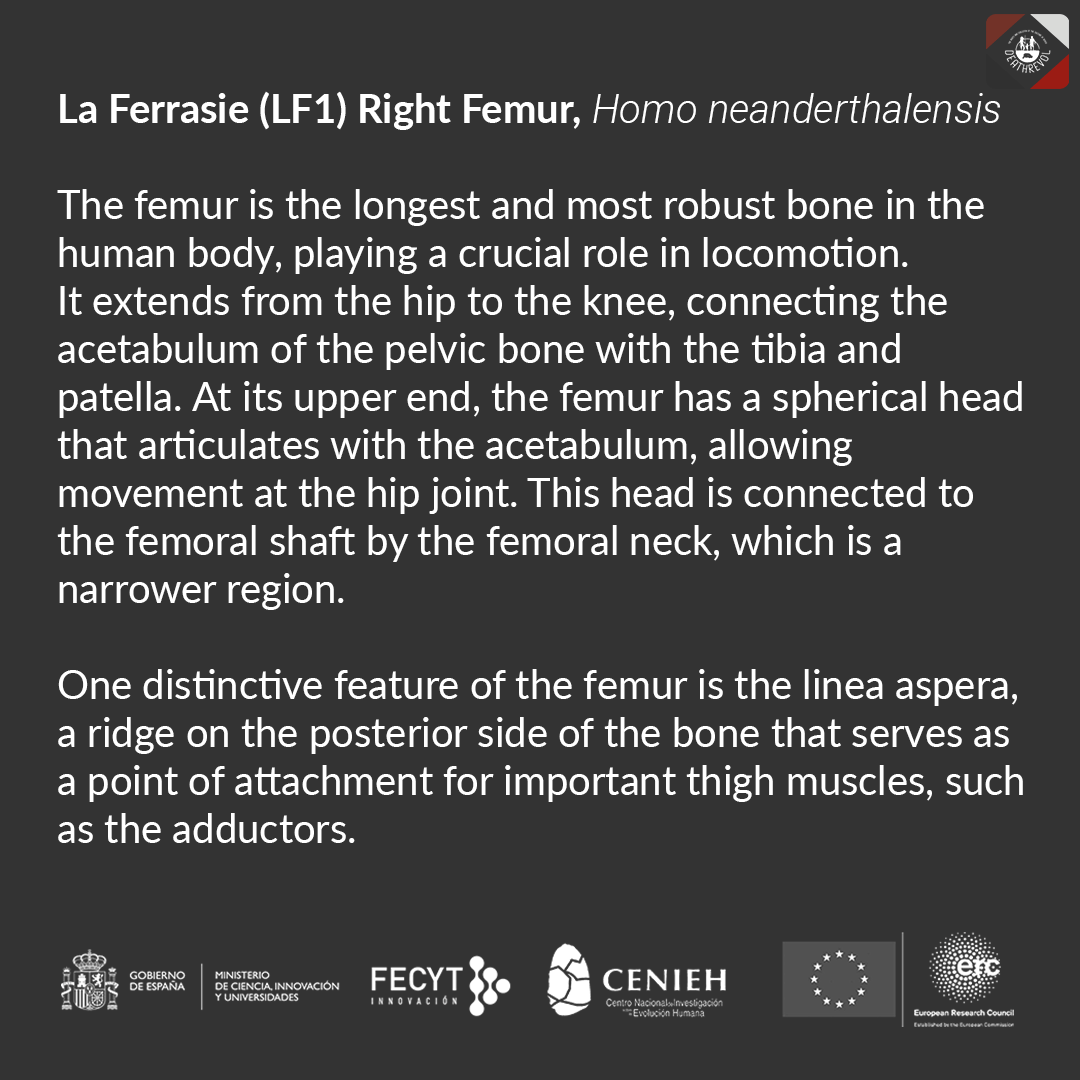

How much do you know about osteology? In the question of this week of our trivial game, we wanted to know if you would know how to recognize a femur from a tibia or a humerus. Here is the full answer!

If you want to learn more about the site where this femur was found, you can visit the “sites” section of our website.

NOBODY´S LAND?_JAVIER LLAMAZARES

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_MANUEL ALCARAZ-CASTAÑO: ENDSCRAPER

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_VIRGINIA MARTÍNEZ PILLADO

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_SAMUEL CASTILLO

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_MANUEL ALCARAZ-CASTAÑO: BLADELET

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_MANUEL ALCARAZ-CASTAÑO

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_ADRIÁN PABLOS

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807

NOBODY´S LAND?_NOHEMI SALA

You can find more information here: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ado3807